Programming with Python

Writing numerical models with Python

Learning Objectives

- Explain what a for loop does

- Correctly write for loops to repeat simple calculations

- Trace changes to a loop variable as the loop runs

- Trace changes to other variables as they are updated by a for loop

- Write conditional statements including

if,elif, andelsebranches - Correctly evaluate expressions containing

andandor

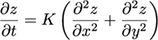

Many members of our community focus on developing numerical models to study how landscapes evolve over time. The simplest and most commonly used transport law used to capture the evolution of hillslopes is a diffusion equation:

where z is elevation, x is the horizontal distance, and K is a landscape diffusion coefficient.

After solving the equation, we’ll find that the elevation of a point at any timestep depends on the elevation of that point and its two neighbors at the previous timestep

Finite difference methods

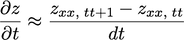

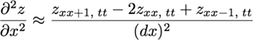

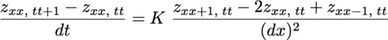

We can solve partial differential equations using finite difference methods by replacing the spatial and time derivatives with approximations that use the gridded data. xx is the index along an array of x positions and tt is the timestep.

The time derivative ∂z/∂t can be approximated using a forward difference:

The second spatial derivative can be approximated by combining a forward and a backwards difference:

The diffusion equation can then be rewritten as:

We can rearrange this equation to solve for the elevation z at position x at timestep t + 1:

Diffusion in 1D

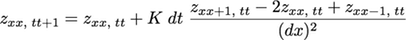

Let’s start by simulating the evolution of a 1D profile across our dataset due to diffusion. First, we need to load libraries and import the dataset. We can then extract a profile across the DEM:

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

topo = np.loadtxt('data/topo.asc')

profile = topo[:,120] # at some arbitrary position

plt.plot(profile, 'k*-')

This is the topography at time t = 0. We will be able to calculate the topography at time t = dt at every point in the array with the equations we derived above.

Let’s create a new numpy array where we can store the new elevation values. The numpy function zeros_like() creates an array that’s the same shape as another array and where every value is zero:

newProfile = np.zeros_like(profile)

print profile.shape, profile.max()

print newProfile.shape, newProfile.max()(500,) 3668.7078

(500,) 0.0Using the finite difference diffusion equation we derived above, we know that the new elevation value of any point along the profile will depend on the elevation values of that point and its two neighbors at the previous timestep.

Since they only have one neighbor each, we have to decide what to do about the first and last cells in the profile. The simplest solution is to keep their elevation fixed and not let them evolve:

newProfile[0] = profile[0]

newProfile[-1] = profile[-1]We can use the diffusion equation to calculate the elevation of the rest of the profile after one timestep.

Let’s start by solving the equation for only one cell. For the cell with index 1, it looks like this:

K = 1

dt = 1

dx = 2 #meters

newProfile[1] = profile[1] + K * dt * (profile[2] - 2 * profile[1] + profile[0]) / dx**2

print profile[0:3]

print newProfile[0:3][ 3080.0466 3082.6816 3085.4751]

[ 3080.0466 3082.721225 0. ]The value of dx is the cell spacing in the topo raster. We chose dummy values for K and dt.

The equation for the elevation of the cell with index 2 is very similar:

newProfile[2] = profile[2] + K * dt * (profile[3] - 2 * profile[2] + profile[1]) / dx**2

print profile[0:3]

print newProfile[0:3][ 3080.0466 3082.6816 3085.4751]

[ 3080.0466 3082.721225 3085.565775]We could keep doing this for every single cell in the array, but it would get boring very quickly. The code would also not scale very well, since we wouldn’t be able to use it for longer or shorter profiles. It would also be very fragile - it’s very, very likely that we would accidentally introduce an error into the code by mistyping something.

For loops

Automating repetitive tasks is best accomplished with a loop. A for loop repeats a set of actions for every item in a collection (every letter in a word, every number in some range, every name in a list) until it runs out of items:

word = 'lead'

for char in word:

print charl

e

a

dThis is shorter than writing individual statements for printing every letter in the word. It it also robust - it scales to longer or shorter words without any trouble:

word = 'aluminium'

for char in word:

print chara

l

u

m

i

n

i

u

mword = 'tin'

for char in word:

print chart

i

nThe script uses a for loop to repeat an operation — in this case, printing — once for each thing in a sequence. The general form of a loop is:

for item in collection:

do things with itemA for loop starts with the word “for”, then the name of the loop variable, then the word “in”, and then the collection or sequence of items to loop through. We can call the loop variable anything we like.

In Python, there must be a colon at the end of the line starting the loop. The commands that are run repeatedly inside the loop are indented below that. Unlike many other languages, there is no command to end a loop (e.g. end for): the loop ends once the indentation moves back.

Here’s another loop that repeatedly updates a variable:

length = 0

word = 'elephant'

for letter in word:

length = length + 1

print 'There are', length, 'letters in', wordThere are 8 letters in elephantIt’s worth tracing the execution of this little program step by step. Since there are eight characters in ‘elephant’, the statement inside the loop will be executed eight times. The first time around, length is zero (the value assigned to it on line 1) and letter is “e”. The code adds 1 to the old value of length, producing 1, and updates length to refer to that new value. The next time the loop starts, letter is “l” and length is 1, so length is updated to 2. Once there are no characters left in “elephant” for Python to assign to letter, the loop finishes and the print statement tells us the final value of length.

Note that a loop variable is just a variable that’s being used to record progress in a loop. It still exists after the loop is over (and has the last value it had inside the loop). We can re-use variables previously defined as loop variables, overwriting their value:

letter = 'z'

for letter in 'abc':

print letter

print 'after the loop, letter is', lettera

b

c

after the loop, letter is cFrom 0 to N

Python has a built-in function called range that creates a sequence of numbers. Range can accept 1-3 parameters. If one parameter is passed, range creates an array of that length, starting at zero and incrementing by 1. If 2 parameters are passed, range starts at the first and ends just before the second, incrementing by one. If range is passed 3 parameters, it starts at the first one, ends just before the second one, and increments by the third one. For example, range(3) produces a list with the numbers 0, 1, 2, while range(2, 5) produces 2, 3, 4, and range(3, 10, 3) produces 3, 6, 9.

Using range, write a loop that prints the first 3 natural numbers:

1

2

3Solution

for i in range(1,4):

print iComputing powers with loops

Exponentiation is built into Python:

print 5**3

125Write a loop that calculates the same result as 5 ** 3 using just multiplication (without exponentiation).

Solution

result = 1

for i in range(0,3):

result = result * 5

print resultTurn a string into a list

Use a for-loop to convert the string “hello” into a list of letters:

["h", "e", "l", "l", "o"]Hint: You can create an empty list like this:

my_list = []Bonus: Once you are done, try casting a string as a list and see what happens.

Solution

my_list = []

for char in "hello":

newstring = char + newstring

print my_listReverse a string

Knowing that two strings can be concatenated using the + operator, write a loop that takes a string, and produces a new string with the characters in reverse order, so 'Newton' becomes 'notweN'.

Solution

newstring = ''

oldstring = 'Newton'

for char in oldstring:

newstring = char + newstring

print newstringComputing the value of a polynomial (Advanced)

The built-in function enumerate takes a sequence (e.g. a list) and generates a new sequence of the same length. Each element of the new sequence is a pair composed of the index (0, 1, 2,…) and the value from the original sequence:

for i, x in enumerate(xs):

# Do something with i and xThe loop above assigns the index to i and the value to x.

Suppose you have encoded a polynomial as a list of coefficients in the following way: the first element is the constant term, the second element is the coefficient of the linear term, the third is the coefficient of the quadratic term, etc.

x = 5

cc = [2, 4, 3]

y = cc[0] * x**0 + cc[1] * x**1 + cc[2] * x**2Write a loop using enumerate(cc) which computes the value y of any polynomial, given x and cc.

Solution

y = 0

for i, c in enumerate(cc):

y = y + x**i * cLooping through the profile

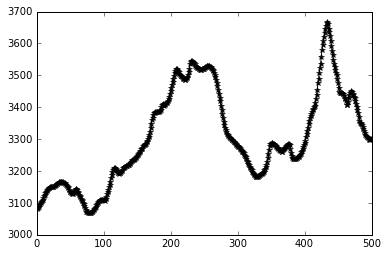

Instead of writing the same equation for each cell in the profile, we can use a for loop that runs the equation for each of the interior cells.

Let’s write a for loop that calls each cell of the profile by its index. Since we are fixing the elevation at the boundaries, our loop should only call cells with indices 1 through len(profile)-1:

for i in range(1,len(profile)-1):

# an equation in parentheses can be split into multiple lines!

newProfile[i] = (profile[i] +

K * dt * (profile[i+1] - 2 * profile[i] + profile[i-1])

/ dx**2)

plt.plot(profile - newProfile)

By plotting the difference between the old and new profiles, we can confirm that our for loop acted along the full length of the profile.

We now have all the pieces to write a script that will evolve the profile by one timestep:

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

topo = np.loadtxt('data/topo.asc')

profile = topo[:,120]

K = 1

dt = 1

dx = 2 # meters

newProfile = np.zeros_like(profile)

newProfile[0] = profile[0]

newProfile[-1] = profile[-1]

for i in range(1,len(profile)-1):

newProfile[i] = (profile[i] +

K * dt * (profile[i+1] - 2 * profile[i] + profile[i-1])

/ dx**2)One timestep is not enough time for the topographic profile to evolve much. We could increase the value of dt, but we can’t change it much before the code becomes numerically unstable. Instead, we want to run our code repeatedly so the profile can change gradually. We can wrap it all in another for loop that steps through time:

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

topo = np.loadtxt('data/topo.asc')

profile = topo[:,120]

K = 1

dt = 1

dx = 2 # meters

maxt = 10

for t in range(0,maxt,dt):

newProfile = np.zeros_like(profile)

newProfile[0] = profile[0]

newProfile[-1] = profile[-1]

for i in range(1,len(profile)-1):

newProfile[i] = (profile[i] +

K * dt * (profile[i+1] - 2 * profile[i] + profile[i-1])

/ dx**2)There is a serious problem with this script: the time loop is always calculating the evolution of the original topography, not the new profile! We need to rewrite our script so the “new” profile becomes the “old” profile before going around the loop again.

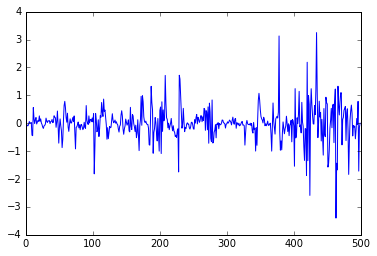

Because numpy arrays are immutable objects, we need to make a true copy of the new profile instead of just using the equal sign. Let’s also add a plotting function so we can see how the profile changes over time:

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

topo = np.loadtxt('data/topo.asc')

profile = topo[:,120]

K = 1

dt = 1

dx = 2 #meters

maxt = 50

plt.plot(profile)

for t in range(0,maxt,dt):

newProfile = np.zeros_like(profile)

newProfile[0] = profile[0]

newProfile[-1] = profile[-1]

for i in range(1,len(profile)-1):

newProfile[i] = (profile[i] +

K * dt * (profile[i+1] - 2 * profile[i] + profile[i-1])

/ dx**2)

profile = newProfile.copy()

plt.plot(profile)

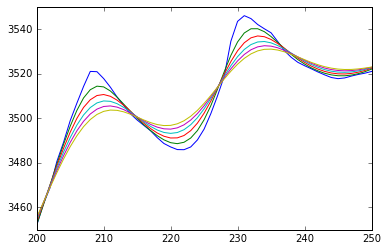

plt.xlim((200,250)) # to focus in on the detail

plt.ylim((3450,3550))

Numerical instabilities

Consider three cells somewhere along the profile where the middle cell is the lowest. From the diffusion equation, know that the two outer cells would drop in elevation over time while the middle one would move up.

- What will the profile look like after one timestep if the value of

dtis very (very!) large? (Hint: Stop thinking of the real world and look at the equation. What doesdtdo to each term?)

Solution

The timestep dt is multiplied by the change in elevation per unit time. The change in elevation will be larger for larger timesteps. If the timestep is very large, the equation will calculate the total change over the timestep based only on the rate of change at the beginning of the timestep, even if, in real life, the rate of change would have decreased over the same period of time. As a result, the new elevations might “overshoot”, changing the three cells from a valley to a hill. This can lead to a numerical instability.

We had to zoom into a small section of the profile to see that the topography was evolving. Because we are plotting every time it goes around the time loop, though, there are too many lines and they are too close together to differentiate between the different profiles.

Let’s run the plotting commands every 10 timesteps instead. There are several ways we can detect when 10 timesteps have passed:

Add a counter that increases by 1 every time the time loop goes around. When the counter is equal to 10, a new plot is created and the counter resets to 0.

The value of the loop variable

twill be divisible by10*dtevery 10 timesteps. The Modulus operator%divides two numbers and returns the remainder, so the operationt%(10*dt)will be equal to zero every 10 timesteps.

Both options require that our script choose to run some commands if one condition is True and others if the condition is False.

Making Choices

When analyzing data, we’ll often want to automatically recognize differences between values and take different actions on the data depending on some conditions. Here, we’ll learn how to write code that decides if some conditions are met.

Conditionals

We can use an if statement to running different commands depending on whether some condition is True or False:

num = 42

if num > 100:

print 'greater'

else:

print 'not greater'

print 'done'not greater

doneWe use the keyword if to tell Python that we want to make a choice. If the test that follows the if statement is true, the commands in the indented block are executed. If the test is false, the indented block beneath the else is executed instead. Only one or the other is ever executed – a conditional statement cannot be simultaneously True and False!

Conditional statements don’t have to include an else. If there isn’t one, Python simply does nothing if the test is false:

num = 42

print 'before conditional...'

if num > 100:

print num, 'is greater than 100'

print '...after conditional'before conditional...

...after conditionalWe can also chain several tests together using elif, which is short for “else if”. The following Python code uses elif to print the sign of a number. We use a double equals sign == to test for equality between two values:

num = -3

if num > 0:

print num, "is positive"

elif num == 0:

print num, "is zero"

else:

print num, "is negative"-3 is negativeWe can also combine tests using and and or. and is only true if both tests are true:

if (1 > 0) and (-1 > 0):

print 'both tests are true'

else:

print 'at least one test is false'at least one test is falsewhile or is true if at least one test is true:

if (1 > 0) or (-1 > 0):

print 'at least one test is true'

else:

print 'neither test is true'at least one test is trueLet’s add a counter to our script so a line is added to the plot only once every 10 timesteps:

import numpy as np

from matplotlib import pyplot as plt

%matplotlib inline

topo = np.loadtxt('data/topo.asc')

profile = topo[:,120]

K = 1

dt = 1

dx = 2 #meters

maxt = 50

counter = 0

plt.plot(profile)

for t in range(0,maxt,dt):

newProfile = np.zeros_like(profile)

newProfile[0] = profile[0]

newProfile[-1] = profile[-1]

for i in range(1,len(profile)-1):

newProfile[i] = (profile[i] +

K * dt * (profile[i+1] - 2 * profile[i] + profile[i-1])

/ dx**2)

profile = newProfile.copy()

if counter == 10:

counter = 0

plt.plot(profile)

plt.xlim((200,250))

plt.ylim((3450,3550))

How many paths?

Which of the following would be printed if you were to run this code? Why did you pick this answer?

- A

- B

- C

- B and C

if 4 > 5:

print 'A'

elif 4 == 5:

print 'B'

elif 4 < 5:

print 'C'Solution

C gets printed because the first two conditions, 4 > 5 and 4 == 5, are not true, but 4 < 5 is true.

What is truth?

True and False are special words in Python called booleans which represent true and false statements. However, they aren’t the only values in Python that are true and false. In fact, any value can be used in an if or elif. After reading and running the code below, explain what the rule is for which values are considered true and which are considered false.

if '':

print 'empty string is true'

if 'word':

print 'word is true'

if []:

print 'empty list is true'

if [1, 2, 3]:

print 'non-empty list is true'

if 0:

print 'zero is true'

if 1:

print 'one is true'That’s not not what I mean

Sometimes it is useful to check whether some condition is not true. The Boolean operator not can do this explicitly. After reading and running the code below, write some more if statements that use not to test the rule that you formulated in the previous challenge.

if not '':

print 'empty string is not true'

if not not True:

print 'not not True is true'Close enough

Write some conditions that print True if the variable a is within 10% of the variable b and False otherwise. Compare your implementation with your partner’s: do you get the same answer for all possible values of a and b?

Solution

a = 5

b = 5.1

if abs(a - b) < 0.1 * abs(b):

print 'True'

else:

print 'False'You could also just print the output of the conditional statement:

print abs(a - b) < 0.1 * abs(b)This works because the Booleans True and False have string representations which can be printed.

Sorting a List Into Buckets (Advanced)

The folder containing your collaborator’s data files has large data sets with names that start with “survey-”, small ones whose names with “small-”, and possibly other files. Our goal is to sort those files into three lists called large_files, small_files, and other_files. Complete the script below.

Hint: You could you the keyword in or the string method startswith

files = ['survey-summer2017.csv', 'myscript.py', 'survey-summer2016.csv', 'small-01.csv', 'funny_field_photo.jpg', 'small-02.csv']

large_files = []

small_files = []

other_files = []Your solution should:

- loop over the names of the files

- figure out which group each filename belongs to

- append the filename to that list

In the end the three lists should be:

large_files = ['survey-summer2017.csv', 'survey-summer2016.csv']

small_files = ['small-01.csv', 'small-02.csv']

other_files = ['myscript.py', 'funny_field_photo.jpg']Solution

for filename in files:

if 'survey-' in filename:

large_files.append(filename)

elif 'small-' in filename:

small_files.append(filename)

else:

other_files.append(filename)

print large_files

print small_files

print other_filesCounting Vowels (Advanced)

- Write a loop that counts the number of vowels in a character string.

- Test it on a few individual words and full sentences.

- Once you are done, compare your solution to your neighbor’s. How did you handle capitalization?

Solution

vowels = 'aeiouAEIOU'

sentence = 'Mary had a little lamb.'

count = 0

for char in sentence:

if char in vowels:

count += 1

print "The number of vowels in this string is " + str(count)You could also use the string method lower to avoid dealing with uppercase letters:

vowels = 'aeiou'

sentence = 'Mary had a little lamb.'

count = 0

for char in sentence.lower():

if char in vowels:

count += 1

print "The number of vowels in this string is " + str(count)Vectorize your code (Advanced)

Using vectorized math instead of loops in your code will make it run faster. Vectorize your 1D code and compare the speed of the two versions.

To measure how long it takes your code to run, you can use the time library:

import time

t = time.time()

# do stuff

elapsed = time.time() - tDiffusion in 2D (Advanced)

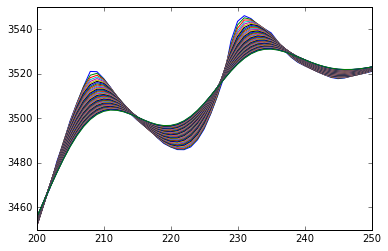

The hillslope diffusion equation in 2D is:

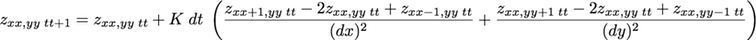

Using finite difference methods, we can write an expression for the evolving topography:

We can rearrange this equation to solve for the elevation z at position xx, yy at timestep t + 1:

Use this equation to model the evolution of the topo array in 2 dimensions.